The Yaga siblings—Bellatine, a young woodworker, and Isaac, a wayfaring street performer and con artist—have been estranged since childhood, separated both by resentment and by wide miles of American highway.

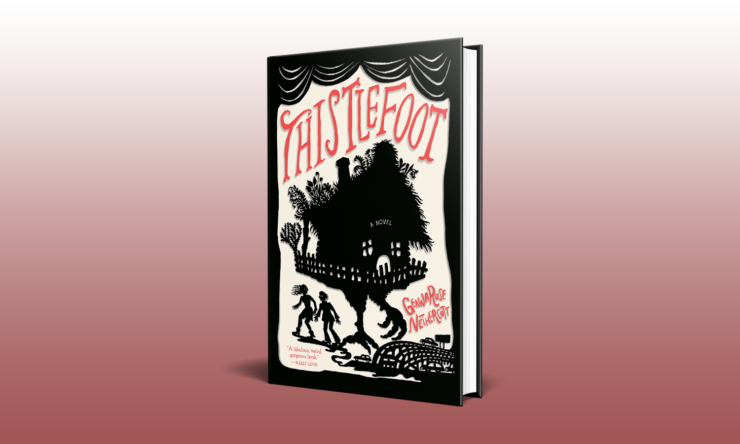

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Thistlefoot by GennaRose Nethercott, out from Anchor on September 13th.

The Yaga siblings—Bellatine, a young woodworker, and Isaac, a wayfaring street performer and con artist—have been estranged since childhood, separated both by resentment and by wide miles of American highway. But when they learn that they are to receive a mysterious inheritance, the siblings are reunited—only to discover that their bequest isn’t land or money, but something far stranger: a sentient house on chicken legs.

Thistlefoot, as the house is called, has arrived from the Yagas’ ancestral home in Russia—but not alone. A sinister figure known only as the Longshadow Man has tracked it to American shores, bearing with him violent secrets from the past: fiery memories that have hidden in Isaac and Bellatine’s blood for generations. As the Yaga siblings embark with Thistlefoot on a final cross-country tour of their family’s traveling theater show, the Longshadow Man follows in relentless pursuit, seeding destruction in his wake. Ultimately, time, magic, and legacy must collide—erupting in a powerful conflagration to determine who gets to remember the past and craft a new future.

Before I was house, I was a baby chick, cracked loose from an egg. It may be difficult to imagine a strong-walled, thick-roofed structure like me as a hatchling—but it’s true. That’s how the story goes, anyway, so that’s how I’ll tell it:

A hen sat on her roost in the dimming light. This hen had no name, no lineage to speak of, no story of her own save for this one I am telling you now. She had been bred for laying and had known nothing save for the small farm where she was raised. The farm was in a Russian shtetl called Gedenkrovka, in what is now Ukraine. It was near spring. The hen heard a goat bray on the edge of the farmland. She shook rain from her feathers. As she sank into the hay’s sweet musk, a song came to her, though she, being a hen, did not know what a song was. It was a strange, lilting thing. A tune the farmer had sung as he had combed the henhouse for speckled brown eggs the day before. The words of the song, I’m sorry to say, have been lost to time. You may write your own lyrics if you like. Outside the henhouse, a light rain fell. The hen felt the laying coming on, so she bedded down deep in the hay, and let an egg loose into the world. Thus, I began. And what a beginning!

Buy the Book

Thistlefoot

Can you imagine what the hen thought when she saw me? First, my tiny golden feet cracking through the shell, all as it should be. Then the rest of me: chimney and gate, small wooden doors, windows blue with glass. The hen, my mother, she spooked too easily. She looked at me and didn’t see a bird at all. Flapped squawking from the roost, they say, so frightened that she ran right out into the night and straight into the town butcher Reb Leiser’s knife. Don’t pity me for losing my mother. I’m not sentimental. She wasn’t my real mother, my heart mother, anyway. She was just an ordinary bite of poultry.

There are many stories about my origin. This is one of them, but not the only one. People talk. How they talk! What I can tell you for sure is that I was born already running. I’m still running. I don’t plan to stop.

The hen was right, of course, to doubt my legitimacy as her child. I’ve never been a very good bird. I am, however, an exemplary house.

I differ from regular houses in two primary ways:

- I do not have a foundation. Instead of a foundation, I have two chicken legs, strong and restless as a slingshot.

- I do not reside in a single static I loathe sitting still. If you try to make me sit still, I’ll kill you.

Other than these departures from the norm, you’ll find me perfectly habitable—as long as my guests are friendly, invited, and do not steal anything from the cupboards.

I have one door, on the front. No back door. I had one once, but it was only used by one woman. When she died, the door died, too.

I have a sod roof, overgrown with alfalfa, vervain, basil, turmeric, gingerroot, yellow squash, heirloom tomatoes. Sprigs of horseradish and thyme. A cluster of purple yams. All a family needs to feed itself and a few visitors. In the sun, the lemongrass lengthens. In the moonlight, smoke blooms from me like dark fistfuls of roses—the great cookstove in my belly always lit, always warm. A porch belts my middle, where one might doze or dangle their legs over the edge to feel the dawn air on their knees. A dried owl talon hangs on a rope beside the door. Tug it, and a deep chime will sound to announce your presence. Knocking is useless. I am too plump. The sound would be swallowed up like a fruit fly into a frog’s throat. Tug once if you’re a stranger. Twice for a salesman. Thrice for a friend. Tug four times if you are my one true enemy, finally caught up to me.

Have I ever heard four tugs? No. It’s not for lack of foes— anyone as strange as I am gathers a bushel of them. But none have ever been polite enough to ring the doorbell. They just try to storm in with torches or rifles, pink-faced as fools. No, when my true enemy arrives, I’ll know him by his civil manner. An enemy who bothers to ring the talon fourfold must feel no threat, as he is in no rush, and still makes time for pleasantries. The most dangerous and violent men are the ones who believe they have nothing to fear.

Excerpted from Thistlefoot, copyright © 2022 by GennaRose Nethercott.